Photo credit: Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0

Planning to Manage Water

Whisky is for drinking, and water is for meeting. Lots of meetings. With lots of talking about water. And a lot of slides, with bullet points. Given that, here are the bullet points I wrote after re-reading the 2015 Colorado Water Plan. While the state water plan was updated in 2023, I still think the 2015 plan, and my critique of it, are relevant. The process to develop the 2015 plan was revealing, in a lot of ways, and it galvanized water interests in Colorado on both sides of the river. Here’s what I think you need to know about current water planning in Colorado, as the 2023 water plan didn’t change much, in my opinion.

The Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) is charged with developing water in Colorado, so it is not “wasted” and used by downstream states like Arizona or California. In 2015, the agency released what it called “Colorado’s Water Plan,” a new state water plan, and it updated the plan in 2023. (The 2023 plan was simply called the “Colorado Water Plan” and it refers to the 2015 plan as such, without the apostrophe, and we follow suit here).

The CWCB, a state agency with the Division of Natural Resources, administers the basin roundtables, which are nine groups of water providers and water rights holders organized by river basin that started meeting regularly in 2005. The roundtables are charged with summarizing their basin’s future water needs and available water supplies, and environmental needs in “basin implementation plans.” Both the 2015 and 2023 versions of the Colorado Water Plan function as a summary of the nine roundtable basin implementation plans.[1]

The CWCB is expecting Colorado’s population to grow from five million in 2010 to 7.5 million by 2050 and considers this growth inevitable.[2] It does not say what happens to the growth curve after that. It concludes that Colorado citizens are only willing to practice low to moderate conservation, thus making the case that new water projects will be necessary to meet the looming water gap.

The 2015 Colorado Water Plan summarizes the basin implementation plans without critiquing them. The basin plans called for over 400 new water projects and methods that would divert and store up to 1.5 million more acre-feet, a 20% increase over the 7.5 million acre-feet of dam storage capacity now existing in Colorado.

Each version of the 2015 state water plan (there were three including two preliminary drafts) grew less and less detailed as players in the water sector lobbied the CWCB to bury or tone down controversial subjects. The 2015 plan fails to mention any proposed transmountain diversion projects and devoted only a single small paragraph to the disappearing Ogallala Aquifer, the source of nearly 20% of the water consumed in Colorado.

The 2015 state water plan claimed the four Upper Colorado River Basin states are entitled to 7.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water, failing to mention that this is nearly double what the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming are consuming. The 567-page 2015 plan barely mentions that Mexico is entitled to a share of the Colorado River.

The 2015 plan says that agriculture needed another 1.5 million acre-feet of water but did not address whether this water is available. It downplayed irrigation efficiency, suggesting that it is harmful and could cause Colorado to fail to meet interstate compact obligations.

If the west slope succeeds in building the 1,168,000 acre-feet of additional storage its 2015 basin plans collectively call for, the state water plan does not evaluate the impact this will have on Colorado’s obligation to deliver water to Lake Powell for the Lower Basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada.

The 2015 plan doesn’t meaningfully address the health of Colorado’s rivers, and it emphasizes that environmental enhancements will most likely be adjuncts to “multipurpose” identified projects and processes.

According to the 2015 plan, no more than 320,000 acre-feet can be obtained from municipal conservation—citizens using less—by 2050. That still leaves a water supply gap of 300,000 to 700,000 acre-feet that must be filled by either drying up agriculture or by taking more water from rivers.

The 2015 plan describes concessions that the Front Range is prepared to make to obtain Western Slope approval for a new trans-mountain diversion. These include sharing some of the water developed in a new trans-mountain diversion with the Western Slope, and agreeing to forego diversions in low snow years or when Lower Colorado River Basin states make a Colorado River compact call.

Back in 2013 when Gov. Hickenlooper called on the CWCB to prepare a state water plan, Logan County Senator Don Ament retorted, “We’ve already got a plan; it’s called prior appropriation.”[3] Ament is a farmer and politician from Iliff, which is in northeast Colorado about forty miles from the Nebraska border. He spent twelve years as a legislator and eight more as Colorado’s agriculture commissioner. Ament thinks the people who own the right to use water—irrigators and cities—should be able to decide how and when water can be used with minimal interference from the public. Whoever got the water first gets to control it, and that’s that.

Ament made his remark at a conference held by the Colorado Water Congress, a trade group of water providers, lawyers, and lobbyists that bills itself as “the principal voice of Colorado’s water community.” The group’s conference room is at eye level with the state capitol’s golden dome, apropos since legislators who want to pass water legislation have little chance without the Water Congress’s blessing. One of their agenda topics in a 2013 meeting was how to cease intimidating legislators when they dropped by to discuss their water bills. From January through May, a Water Congress legislative committee starts each week Monday at 8:00 a.m. sharp to review the week’s upcoming water bills. In 2015, its website boasted, “Since 1981 we’ve logged a success rate of 85 percent on state water-related legislation that the Water Congress has endorsed. It’s rare that a bill opposed by our membership is ever signed by a Colorado governor.”[4]

The Water Congress and the rest of Colorado’s water community tend to shy away from any lights shined on their water world. But the public process used to develop the 2015 Colorado Water Plan[5] did serve to put a bright light on Colorado’s tight-knit and low-key water sector. A big giant spotlight had been involuntarily powered on in 2002, when the Colorado River plummeted to its lowest flow in 500 years. At less than six million acre-feet, the 2002 runoff was less than half its average annual flow.[6] The next year Referendum A appeared on the state ballot, calling for $2 billion to build new dams and pipelines. The referendum amounted to a blank check for undefined water projects. Voters crushed the referendum—it lost by two-thirds in practically every county. In response, the state of Colorado, via the CWCB, launched the Statewide Water Supply Initiative in 2004. Known as SWSI, and pronounced “swazhi,” its purpose was to estimate water demands and supplies available to meet them and publish the findings.

Water utility directors want to store enough water to meet at least three years’ municipal needs. As Colorado’s population keeps growing, that target keeps getting more and more elusive. The SWSI plan, first published in 2010, has now morphed into what CWCB calls its “Technical Update,” which was last updated in 2019 and informed the 2023 version of the state water plan. The SWSI water-planning process got revved up in 2005 when the legislature passed the Water for the 21st Century Act,the bill creating the nine roundtables. Four are on the west slope of the Continental Divide and five are on the east slope, creating, and not likely by accident, a Front Range majority of roundtables.[7]

The legislation said the mission of the basin roundtables, which are permanent and independent local public bodies, was “to facilitate continued discussions within and between basins on water management issues and to encourage locally driven collaborative solutions to water supply challenges.” The west slope, or as it often called, the Western Slope, refers to the part of Colorado that is west of the Continental Divide and drains into the Colorado River system. The east slope, or as it is often referred to, the Front Range, is the part of the state that drains into the South Platte, Arkansas, and Rio Grande river systems.

The Front Range itself is technically what geologists call the mountain range that extends from Casper, Wyoming, to Pueblo, Colorado, but I use it to refer to the urban corridor that now sprawls from Fort Collins to Pueblo. I tend to use “Western Slope” and “Front Range” to talk about the people and communities on either side of the Divide, and “west slope” and “east slope” to refer to the geographic landscape of the two areas, as in, “the people of the Western Slope are proud to live on the west slope of Colorado, as the people of the Front Range are proud to live on the state’s east slope.”

Eight of the roundtables are organized geographically around river drainages in the state, and their boundaries are generally consistent with the “water divisions” created by the state to administer water rights, both by “division engineers” and by water courts, which are overseen by district court judges. The five east slope roundtables are the South Platte Basin Roundtable (Division 1), the Arkansas Basin Roundtable (Div. 2), the Rio Grande Basin Roundtable (Div. 3), the Metro Basin Roundtable (in Div. 1), and the North Platte Basin Roundtable (in Div. 6). Unlike the other roundtables, the Metro Roundtable is not geographically based on a river basin but on the boundaries of the Denver metro area. The Metro Roundtable, which meets at Denver Water’s headquarters, includes the City and County of Denver. It also includes the counties of Arapahoe, Douglas, Jefferson, Adams and El Paso, and the cities of Aurora, Broomfield, Thornton, and Englewood, among others. The Metro Roundtable was a political accommodation because that’s where over half of the people live in Colorado. Its boundaries are wholly within the South Platte River basin, and the Metro Roundtable usually moves in lockstep with the South Platte Roundtable, including preparing a joint basin implementation plan and sharing a website.

The west slope roundtables are the Gunnison Basin Roundtable (Div. 4), the Colorado Basin Roundtable (Div. 5), the Yampa-White-Green Basin Roundtable (Div. 6), and the Southwest Basin Roundtable (Div 7). (The Southwest roundtable was called the “Dolores, San Miguel, and San Juan Basins Roundtable” in the originating legislation).

The roundtables each have their own bylaws, set their own agendas, and meet five to ten times a year in public meetings that must adhere to state’s open meeting laws. Each roundtable has about 35 to 40 voting members. Roundtable membership is comprised, by design, of representatives of the counties, cities, water rights owners (irrigators), water utilities, and water managers in each basin. And in each roundtable, there is one seat designated for an environmental representative, and one seat for a recreational representative.

“Water buffaloes,” or experts who work in the water sector in some capacity, are well-represented on the roundtables. They are most often there in their professional roles as water lawyers, hydraulic engineers, water managers, and/or water policy gurus.

In addition to being an attorney (but not a water lawyer) and a CPA, I am a kayaker. I showed at the first Colorado basin roundtable meeting in 2005, at the suggestion of my state representative at the time, and I volunteered to serve as the recorder/secretary and to keep the minutes so I could have a seat at the table. After several years, I was appointed as the recreation representative and became eligible to participate in roundtable votes. I continue to hold both positions. (I now receive a $200 stipend for each set of minutes I create as secretary of the roundtable, receiving about $1,200 a year, from the Colorado Water Conservation Board, or CWCB, which funds the roundtables with state money.) I have always had an interest in water, and live between Basalt and Carbondale, about a mile north of the Roaring Fork River, which flows into the Colorado River in Glenwood Springs.

To have a vote on the Colorado Roundtable, or on any roundtable, members must either represent a county, a municipality, a water conservation or water conservancy district, be appointed by the legislature, or be an “at large” member appointed by the roundtable itself, by virtue of holding a seat designated for, respectively, a domestic water provider, an owner of water rights, or by representing the environment or recreation. The public can attend the roundtable meetings and speak up and participate, but not vote. Most of the votes taken are on proposed water grants, which are funded by the state via the CWCB. The CWCB serves as something of a parent organization for the roundtables, but technically the roundtables are independent, and not directly under the CWCB’s control, although it sure seems like they are.

In 2024, the CWCB published a draft of the CWCB Guide, available on its website, that seeks to set the record straight about what powers the roundtables have and don’t have. The guide says, “The basin roundtables are not official ‘entities.’ As such, they cannot be fiscal agents, do not have bank accounts and do not hold discretionary money (e.g. cannot contract work or materials).” This seems to differ a bit from the language in HB 1177, which states that the roundtables are “local public bodies” with their own bylaws. But the Guide states that “outside of their own bylaws, roundtables do not create policy although they frequently inform it through coordination with the Interbasin Compact Committee and/or the CWCB Board - especially through their CWCB Basin Director, but also in coordination with CWCB staff. As they do not have legal representation, roundtables cannot enter into a formal executive session and they cannot create legally binding actions. Additionally, neither the roundtable nor a roundtable representative can take an official position on legislation.” The CWCB does seem to treat the roundtables like children, doesn’t it? In any event, the CWCB Guide does acknowledge that “roundtable meetings are meant to be open, inclusive, accessible, properly noticed, documented, live-streamed, and allow time for public comment.”

For the uninitiated, roundtable meetings can sometimes be opaque, confusing, and dull. But for water buffaloes, or water geeks, the meetings are informative and a good place to build relationships in Colorado’s water world. Each basin roundtable is also charged with estimating how much water is needed for future population growth, whether this water is available, and how storing or diverting it could impact the environment. The roundtables list and describe their water supplies and needs in “basin implementation plans,” also called “BIPs” or “basin plans.” They are a roadmap to future water development in Colorado because they list proposed projects, both consumptive and environmental.

What the public considers as environmental or riparian needs are called “nonconsumptive needs” because they do not consume river flows. Hydroelectric projects are an example of nonconsumptive projects since they use the river’s flow to spin turbines, but the water isn’t consumed, it pours back into the river. In short, nonconsumptive projects leave water in the river while consumptive projects take water out of the river. Water diverted from rivers is either consumed or makes its way back to the river underground in what irrigators and engineers call “return flows.” Water is consumed by plants through evapotranspiration or by evaporating off a water body like irrigation ditches and lakes. Evaporated water ultimately makes its way back to earth through snow or rainfall, but not directly to the river it was diverted from. It is said return flows do make their way back to the river, at some point, but the intervening stretches between diversion and return point can suffer from minimal flows. Return flows can also damage water quality by depositing dissolved pesticides and salts in the river. It is common, however, for irrigators to claim that return flows are the best thing for a river, to the point where it seems they believe the best thing you can do for a river is divert as much of its water as you can. Seriously.

Consumptive use typically damages rivers because water is diverted from the river. However, nonconsumptive projects can also damage rivers. For example, the water that powers the Shoshone hydropower plant in Glenwood Canyon comes from a 12-foot-tall dam all-the-way across the Colorado River at Hanging Lake, upriver from Glenwood Springs. The dam diverts water into a pipe on the cliffs above Interstate 70 and then, two miles later, sends it down the cliff in penstocks into the plant. The river-wide dam prevents any fish from getting upstream, and the alternating high and low flows below the dam wreak havoc with the riparian environment. When water flows drop in the river, typical in the winter, a sterile rocky channel appears for two long miles in the famed Colorado River. Water providers and irrigators do not like the term “environmental needs,” but I use the term because the public knows what it means. There is no greater need for rivers in the west than environmental needs, which almost always translate to leaving more water in the river. But referring to them as environmental needs suggests that all is not right with rivers, so the state and the water community uses the term “nonconsumptive.”

Anyway, the various basin plans tend to be detailed—the 2015 Arkansas basin plan alone listed over 500 proposed water projects. But it was the first time that state had catalogued both what is needed to support population growth, and what river reaches are at risk and what is needed to restore them. The first basin plans informed the 2015 Colorado Water Plan, a 492-page tome released in November 2015, but the most controversial water projects themselves were barely described in either the basin implementation plans or in water plan itself. Perhaps the South Platte Roundtable’s most controversial project in the 2015 water plan was the Northern Integrated Supply Project, or NISP, which centers on building the 170,000 acre-foot Glade Reservoir near Fort Collins to capture what is left of the peak snowmelt flow in the Poudre River. Nothing came back when I searched for “NISP” or “Northern Integrated Supply Project” in the 2015 Colorado Water Plan.[8] Ken Neubecker, who was the Colorado Roundtable’s environmental representative from 2005 to 2021, said at the time it was because the state feared that listing NISP in the water plan could be interpreted as though the state was sanctioning it. In 2024, the CWCB agreed to loan Northern Water $100 million to help pay for the project, most of which will be spent to build Glade Park Reservoir near Ted’s Place north of Fort Collins, which is a whole other level of sanctioning!

NISP made it into the updated 2022 South Platte Basin Implementation Plan, which described it as a “collaborative project with a goal of providing “40,000 acre feet of new, reliable water each year.”[9] It will store 170,000 acre feet of water in Glade Park Reservoir, which will stretch for five miles and inundate 1,600 acres, making it one of the larger reservoirs constructed in Colorado.[10] It will also reconnect more than two miles of river habitat for fish that were blocked by a water diversion structure adjacent to Watson Lake that takes water from the Poudre River, an environmental benefit that qualifies the project as “collaborative.”[11]

Each roundtable listed the expected costs of its major projects in a tidy box in the 2015 state plan, highlighting the need for money to produce the water supplies needed for Colorado’s next population doubling. But the little boxes did not describe what the projects were.

Figure 4.1 Box from Arkansas Basin BIP, “Arkansas Basin At a Glance”

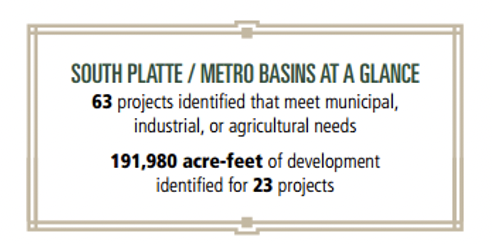

Figure 4.2 Box from South Platte/Metro Basins, “South Platte/Metro Basins at Glance”

Neither the 2015 Colorado Water Plan nor the Arkansas basin plan described the four projects that needed $345 million, nor the seventeen projects proposed to deliver 166,500 more acre-feet listed in the box called “Arkansas Basin at a Glance.”[12] The “South Platte/Metro Basins at a Glance” box did not even mention expected future costs, despite the fact that the twenty-three projects proposed to develop 191,980 acre-feet—enough water for over 1.5 million new residents—have been on the planning board for decades.[13]A clue about this can be gleaned from the March 2016 staff report to the CWCB directors, where a table on page 22 of a 135-page memo indicates that $100 million has been earmarked for NISP. There is no better place to hide information than in words and numbers, preferably lots of them, or by coining new words like “NISP” that really don’t mean anything at all. The “Northern Integrated Supply Project” could just as easily describe Walmart’s latest supply chain upgrade or an extension of the Keystone pipeline. In January 2024, the CWCB authorized a loan of $100 million to develop NISP, eight years after the March 2016 CWCB memo mentioned $100 million was needed to develop it. This delay is not unusual. Steve Harris, an engineer that helped develop the Animas La Plata dam project and a prominent member of the Southwest Roundtable, talked repeatedly of “water time,” the delays that were common with complicated water projects.

Each roundtable updated their wish list of basin projects in 2021, identifying $20.3 billion in water project costs. The South Platte and Metro roundtables tab came in at $9.8 billion, the most expensive project list, followed by the Colorado Roundtable with a project price tag of $4.1 billion. Since 2015, the CWCB has spent some $500 million in grants and loans helping fund water projects across the state, according to Russ Sands, who is the section chief for water supply planning at the agency.[14] Here’s what the updated roundtable basin implementation plans are saying about the water needs in their basins and note how many of them acknowledge that rivers in their basin will be suffering from low water.

The Arkansas River Basin is suffering from “extreme hydrology” and the declining Southern High Plains Aquifer, part of the Ogallala Aquifer. It says that switching from flood to sprinklers will require 30,000 to 50,000 more acre feet, and its flow tool shows that climate change will put rivers at risk. [15]

The Colorado River Basin, which irrigates 206,700 acres, says instream flows may not be met in July and August.[16]

The Gunnison Basin, where 97% of all water is used to irrigate 250,000 acres, says that protecting existing users is its main goal.[17] It reports that beef contributes $100 million to the economy while recreation contributes $461 million.

The North Platte Basin Roundtable, which irrigates 113,600 acres through 400 irrigation ditches, reports that maximizing the consumptive use of water is its main goal.[18] It says that climate change will put its rivers at risk.

The Rio Grande Basin, whose water supplies irrigate 520,000 acres in a basin receiving 8 inches of precipitation a year and which has been over-appropriated for 125 years, says that unsustainable groundwater pumping will lead to degraded river supplies.[19]

The South Platte Basin, which has 850,000 irrigated acres, says its main goals are increasing storage, easing dam permitting restrictions, meeting the municipal supply gap, and protecting agriculture. It also bemoans the loss of corn growing in the Republican River Basin, where 550,000 acres of groundwater pumping, seen as green circles from above, will be slowly retired because the Ogallala Aquifer continues declining. It could also be due to the 3 inches of precipitation it gets during the growing season from April through October.[20]

The Southwest Basin, whose population is expected to grow 16% to 161% by 2050 from retirees and recreation-seekers, the fastest growth in the state, says that we must legally acknowledge agricultural water rights and that “streamflows may not be met” due to agricultural water uses. It says that peak flows will decline with climate change and that rivers will suffer.[21]

The Yampa-White-Green Basin says that it must protect agricultural uses and increase storage since agriculture is a primary focus and that cattle ranching is a major economic driver. It says that closing the coal-fired power plants in Craig and Hayden will pose a serious economic challenge, and that the flow tool shows that instream flows will not be met as a result of climate change.[22]

Per House Bill 05-1177, each roundtable is to appoint two members to an Interbasin Compact Committee, or IBCC, which meets several times a year. The IBCC is charged with creating “a negotiating framework and foundational principles to guide voluntary negotiations between basin roundtables.” The governor also appoints six members to the IBCC, and no more than three can be registered as Democrat or Republican. The six must be from geographically diverse parts of the state and have expertise in environmental, recreational, local governmental, industrial, and agricultural matters. Both the Senate and House agricultural, natural resources, and energy committees each appoint a member as well.[23] The IBCC members had spent years debating conditions that had to be met before a new or expanded transmountain diversion could send water to the Front Range from the Western Slope, dubbing the resulting working agreement the “Conceptual Framework.” It would have been too pedestrian to call it what it was, “Conditions for Future Transmountain Diversions.” The IBCC spent so much time debating these conditions that I believe SWSI, the roundtables, the IBCC meetings, and the 2015 Colorado Water Plan were all targeted at finally getting a big water project passed on statewide level. And if the public is asked to vote on a big water project included in a state water plan, which has not yet occurred, we will likely be told that the project was forged after hundreds of meetings and that environmental and recreation representatives were there every step of the way. It’s true those representatives were in those meetings. I estimate I’ve been to over 300 water meetings in the last 20 years. But while the reps may well have been at such meetings, did they speak up? And were their views taken into consideration? It’s hard being the lone voice in the room all the time.

The Colorado legislature allocates funding to the CWCB to award as grants, primarily from its Water Supply Reserve Account, and so the grants are called “WSRA grants.” The CWCB then splits up the grant funding to the roundtables, without giving them the real dollars, just the amounts, and then tasks the roundtables with reviewing grant applications against their theoretical bucket of funds. The roundtables then make recommendations to the CWCB board, which formally distributes the actual funding to the grant recipients. After the 2015 Colorado Water Plan was published, the Colorado legislature in 2017 began appropriating funds for another bucket of funds called “Colorado Water Plan” grants to fund projects and studies identified in the basin plans.[24] Each roundtable now receives $300,000 a year for state WSRA grants.[25] From 2006 to 2023 the roundtables allocated $255,000 per year in such grants[26] Today, much of our attention at roundtable meetings is spent deliberating grant proposals, as something of a courtesy to the CWCB board members. Roundtables first review both types of state grants, applying their local knowledge to the decision making, but final approval rests with the CWCB board, whose members tend to take a hands-off approach to most grants and routinely approve roundtable recommendations. Water providers and irrigators make most of these grant requests, and environmental groups also regularly submit proposals, such as to fix a degraded stretch of river or to draft “stream management plans” that catalog environmental and other needs.

The Colorado Roundtable has awarded grants to do things such as purchase water in the Vail Ditch to augment Colorado River flows in Grand County; to improve crumbling dams or irrigation diversion structures; to line irrigation ditches in Pitkin and Eagle counties; to restore the Swan River above Breckenridge that was literally turned upside-down by hydraulic miners starting in the 1860s; and for scientists at The Nature Conservancy to develop a flow evaluation tool to indicate when rivers are at risk from excess diversions. Such grants are one of the roundtables’ best features since, for the first time, state funds have been made available to analyze river health. The roundtables themselves are the other best feature. They shed light on how we use water, and move it around, in Colorado. They give the public a view of the process and are far less insular than trade groups like the Colorado Water Congress. (The public can attend the two conferences the Colorado Water Congress produces each year, but the entrance fee is steep and the real business at the conferences seems to occur in private meetings and conversations away from the public conference rooms). Public access is important when it comes to water despite the constant refrain that water rights are private property, because the state’s water is in fact a public resource. The state grants a user the right to use water and put it to a beneficial use under specific conditions – but not to own the water itself.

The 2015 and 2023 state water plans were written by staff at the CWCB with the help of outside contractors and input from the roundtable members. Nine of the ten voting members of the CWCB’s board of directors are appointed by the governor and they represent each of the roundtable basins (the tenth voting member is the director of the state’s Department of Natural Resources, who is hired by the governor). The CWCB directors also serve as non-voting liaisons to their respective roundtables. The CWCB was created by the Colorado legislature in 1937, the year that modern water development began in Colorado. A book by Tom Cech about the history of the CWCB is called Defend and Develop: A Brief History of the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s First 75 Years. The main title, Defend and Develop, neatly summarizes the CWCB’s current mission, as in to “defend” Colorado’s water rights and use from other states, such as those in the lower Colorado River basin, and to “develop,” or put to use, the state’s water. 1937 was a big year for water development in Colorado. It was also the year the U.S. Congress authorized the Colorado-Big Thompson Project to divert 225,000 acre-feet each year from the Colorado River at Grand Lake to Estes Park on the east slope. It was the year both the CWCB and the Colorado River Water Conservation District were created by the state legislature. And it was the year the legislature authorized water conservancy districts, water districts run by local landowners, such as the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District (Northern Water), that receives water from the Colorado-Big Thompson Project.

The CWCB’s mission is to aid "in the protection and development of the waters of the state.”[27] The word “conservation” in Colorado Water Conservation Board refers to conserving water for future development. That typically translates into building dams and diverting water out of rivers so it can be held back and put to beneficial use rather than being “wasted” downstream. To “conserve” water—I cannot emphasize this enough—means storing it in a dam or diverting it out of a river. It does not refer to improving or protecting the natural environment, as in a land conservation easement. The Colorado River Water Conservation District, commonly called “the River District,” is a regional water management and policy organization on the Western Slope. It’s another example of this odd use of “conservation.”

The Colorado River Water Conservation District is not charged with conserving the environment, instead it is charged with protecting and, more recently, developing water resources, which means taking water out of rivers for either irrigation or municipal development. The River District’s board of directors includes a representative from each 15 Western Slope counties within the Gunnison, Colorado, Yampa, and White river basins. The district’s initial charge was to protect Western Slope irrigators from the Colorado Big-Thompson project. It has the most clout in water matters of any government agency on the Western Slope and it is actively involved in all Colorado River matters from Grand Lake to Lake Powell to the Lower Basin.

Water left in streams is not “wasted,” it is maintaining the river ecosystem. We take more water than we need from nearly every river in the West in order to grow hay, usually by flooding fields adjacent to the river. This harms river health in part because flood irrigation is only 30 percent efficient—we divert over three acre-feet from the river for each acre-foot consumed to grow hay. An acre-foot, like it sounds, covers an acre with a foot of water. An acre is about the size of a football field, not including the end zones. Hay and bluegrass lawns consume about 2 acre-feet a year per acre of hay or lawn over the course of the summer growing season. Including the word “conservation” in the names of water agencies can confuse the public. We could end this confusion by renaming the Colorado Water Conservation Board as the Colorado Water Development Board (and similarly recasting every other water provider that uses “conservation” or “conservancy” in its name or mission).

Opaque Plan

The CWCB released the first draft of the 2015 Colorado Water Plan in August 2014, updated it a year later, and delivered the 2015 plan on November 19, 2015. The 2015 water plan summarized each basin roundtable’s need for more water and particularly storage, reflecting the CWCB’s policy to maximize development of state water resources. Reading the 2015 water plan can be frustrating because while it constantly refers to water projects, it does not describe them in sufficient detail to inform the reader. But the plan makes it clear that “the CWCB will continue to support and assist the basin roundtables in moving forward the municipal, industrial, and agricultural projects and methods they identified in their BIPs (basin implementation plans).”[28] By refusing to endorse any specific projects, the 2015 water plan took the political road of least resistance.[29] In some cases it has to, since the basin plans contradict one another.

For example, while the Arkansas basin implementation plan lists taking more water out of the Roaring Fork and Fryingpan rivers, which feed the Colorado River, as its number one storage goal (via what was once called the Preferred Storage Option Plan, or PSOP), the Colorado basin plan said another transmountain diversion should be our last option, the last tool we take out of the box.[30] The 2015 state water plan ducked contradictions like this, mentioning PSOP only once in a table of acronyms. In fact, it failed to discuss in detail any of the proposed dams or projects described in the plan’s “new supply” chapter. In the 2022 update, it lists 361 projects with a price tag of $3.6 billion, but again fails to mention expanding Turquoise and Pueblo reservoirs, for example. One line in the detailed spreadsheet on page 108 of the 2023 water plan describes a goal to “Obtain more storage space in the Basin (Turquoise or Pueblo) to store Derry 3 Water (sic),” but that is the closest the Arkansas BIP gets to describing PSOP.[31]

Water projects can be like submarines, recognizable only to insiders who know they’re out there. To move PSOP forward, water providers in the Arkansas basin stopped calling it “PSOP” and focused instead on promoting the various component parts of the project. Colorado Springs Utilities built the Southern Delivery System, a pipeline transporting water from Pueblo Reservoir north to Colorado Springs. They’re doing PSOP piece by piece and without calling it PSOP. Practically no one on the Western Slope knows who the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservancy District is, but it is in fact the organization that controls the water transported to Pueblo in the Fryingpan-Arkansas project, which delivers water from the Roaring Fork and Fryingpan rivers. Representatives from the Western Slope rarely attend their meetings in Pueblo, including from Pitkin and Eagle counties, which provide the water to Southeastern’s service area in the Arkansas basin. Another stealth Arkansas Basin project is capturing 30,000 acre feet in the Eagle River near Tennessee Pass above Minturn, this time obscured under the title, the “Eagle River MOU.” It gets one mention in the Arkansas Basin Implementation Plan 2022 update on page 104 of Volume 2, described as a “MOU [Memorandum of Understanding] among East and West Slope water users for development of a joint use water project in the Eagle River basis that minimizes environment (sic).”[32] In fact, it’s a plan to capture 165,000 acre feet and to annually divert 20,000 acre feet to be split between Colorado Springs and Aurora, and 10,000 more acre feet to water developers in Eagle County, for decades the second fastest growing county in Colorado.

The common theme throughout the 2015 water plan is that agricultural dry up is unacceptable, population growth is inevitable, cities cannot achieve more than low to medium levels of water conservation, and cooperation is the key to protecting the health of rivers. For longtime roundtable observers, there was little new in the “final” plan—this has been the CWCB’s consistent message since the roundtables started meeting in 2005. The 2015 plan did not explicitly favor new transmountain diversions—it conspicuously ignores them—but it intimates that without them Colorado’s economy will suffer. The final draft mentions “quality of life” eleven times but did not address how exponential population growth or taking still more water out of rivers will affect quality of life.

Consider this passage: “The IBCC and CWCB identified a minimum of low to medium levels of active water conservation practices as a “no-and-low regret.”[33] I calculate that low to medium levels of water conservation translate to annual water use of 164 gallons per person per day—by contrast, Albuquerque citizens use 129 gallons per person per day, and residents in Tijuana and Mexicali south of the California border get by on less than 60 gallons per person per day.[34] The South Platte Roundtable believes that bluegrass lawns are essential to life on the Front Range: “The urban environment is an important component of the quality of life for many South Platte Basin residents. Judgments about the value of the urban environment, including both the need to provide water for irrigated landscape and the vital benefits that landscape provides to citizens and the environment, make the discussions about water supply development needs all the more difficult.”[35] By adopting a low-to-medium municipal conservation goal and by stating that bluegrass lawns are necessary to our quality of life, the inevitable outcome is that farms and rivers in Colorado will continue to dry up.

“No-and-low regrets” is another loaded term, showing up 78 times in the 500-page 2015 state water plan. While never defined, it refers to actions that are politically acceptable to all, a kind of lowest denominator that water buffaloes can live with. For the next state water plan, the “no-and-low-regrets” process is being recast by the CWCB as a “drought contingency” planning process.

We will see what that brings.

Notes

[1] Colorado’s Water Plan, Final 2015 Draft, downloaded May 1, 2016, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/CWP2016.pdf.

[2] Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA), State Demography Office, Births, Deaths, and Migration Spreadsheets: Download population data for all geographies, Regional Components of Change for Colorado 1970-2050, downloaded September 8, 2024, https://demography.dola.colorado.gov/assets/html/coc.html. The 2015 plan expected Colorado’s population could double to 10 million by 2050, but the 2023 plan reduced that to 7.5 million; see, Executive Summary, Colorado’s Water Plan, 2015; and Colorado Water Plan, 2023, page 23.

[3] Public comment made at a Colorado Water Congress meeting on June 4, 2013, to discuss Sen. Schwartz’s defeated irrigation efficiency bill, SB13-019. NASDA, “Don Ament to Retire from Public Service,” Jan. 8, 2007.

[4] “Colorado Water Congress History,” downloaded Mar. 27, 2016, http://www.cowatercongress.org/history.html. After I first the first draft of this chapter, the 85% success rate reference was removed. It can be viewed by searching web.archive.org and viewing the above url as of August 3, 2015.

[5] The 2015 plan was titled “Colorado’s Water Plan,” with an apostrophe and possessive declaration. The 2023 water plan update was called the “Colorado Water Plan,” without the apostrophe. And in the 2023 update, the CWCB also referred to the old 2015 plan as the “Colorado Water Plan,” without the apostrophe, so we follow suit and refer to them both as Colorado Water Plan, or the state water plan.

[6] In the 2002 water year ending 9/30/2002, Reclamation estimates the natural flow of the Colorado River at Lee Ferry was 5,933,609 acre feet. Bureau of Reclamation, Colorado River Basin Natural Flow and Salt Data, CURRENT natural flow data 1906-2020 (Excel file, 1.5 MB) - Updated 12/15/22, at spreadsheet tab AnnualWYTotalNaturalFlow, column W.

[7] House Bill 2005-1177, available at CRS 37-75-101 to 106.

[8] Colorado Water Plan, 2015.

[9] South Platte Basin Implementation Plan, Vol 1, pg. 17, Vol. 2, pgs. 16, 221, Jan 2022.

[10] “Frequently Asked Questions about NISP,” Northern Water, downloaded June 17, 2024. https://www.northernwater.org/NISP/about/FAQs#:~:text=Glade%20Reservoir%20will%20be%205,slightly%20larger%20than%20Horsetooth%20Reservoir.

[11] “Watson Lake Fish Bypass Improving River Habitat,” Northern Water, downloaded June 17, 2024, https://www.northernwater.org/NISP/environmental/watson-lake-fish-bypass#:~:text=in%20your%20browser.-,Helping%20Fish%20Travel%20Upstream,2%20miles%20of%20valuable%20habitat.

[12] Colorado Water Plan, 2015, Section 6.5.1: BIP Identified Municipal, Industrial, and Agricultural Infrastructure Projects and Methods, pg. 6-131.

[13] Id, pg. 6-135.

[14] Smith, J., “Nine Colorado Roundtables submit $20.3B in water project lists, ask for public’s input,” Oct 20, 2021, Water Education Colorado, https://www.watereducationcolorado.org/fresh-water-news/nine-colorado-roundtables-submit-20-3b-in-water-project-lists-ask-for-publics-input/.

[15] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pg. 76-83.

[16] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 86, 91.

[17] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 93-96.

[18] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 101-107.

[19] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 110-115.

[20] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 116-123.

[21] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 124-131.

[22] CWCB, Colorado Water Plan, pgs. 132-139.

[23] CRS Section 37-75-105(1)(a), Interbasin compact committee.

[24] See the CWCB website for more information about Colorado Water Plan grants at: https://cwcb.colorado.gov/funding/colorado-water-plan-grants.

[25] Colorado River Basin Roundtable meeting minutes, November 29, 2021, pg. 2. Prior to 2022, oil and gas severance taxes provide the source of funds for WSRA grants. Severance taxes ebb and flow with oil and gas production, and they’re also at risk of being raided by the governor or the legislature. In 2016 the Colorado Supreme Court held that British Petroleum had been paying too much severance tax in Colorado because the Dept. of Revenue wouldn’t let it deduct its capital improvement costs. The ruling meant Colorado had to send $115 million in tax revenue back to oil producers, which reduced future severance tax revenues by 13 percent. Prentice-Dunn, J., “Oil Companies Successfully Widen Colorado Tax Loophole, Leave Taxpayers on the Hook for $100 Million,” May 10, 2016, Center for Western Priorities, http://westernpriorities.org/2016/05/10/oil-companies-successfully-widen-colorado-tax-loophole-leave-taxpayers-on-the-hook-for-100-million/.

[26] CWCB, Water Supply Reserve Fund 2022-23 Annual Report, 10/31/2023.

[27] See, C.R.S. 37-60-106. The CWCB’s mission is to protect and develop waters of the state for present and future inhabitants. The CWCB represents Colorado in interstate compact negotiations, oversees the Endangered Species Act fish recovery programs, ensures Colorado can use its full Colorado River Compact entitlement, and represents Colorado in the Glen Canyon Adaptive Management Program, which administers releases from Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead.

[28] Colorado Water Plan, 2015, Sec. 6.5.4: Maintenance of Existing Projects and Methods, pg. 6-155.

[29] Colorado Water Plan, 2015, Sec. 6.2: Meeting Colorado’s Water Gaps, pg. 6-15.

[30] The Arkansas roundtable Basin Implementation Plan lists the Preferred Option Storage Plan (PSOP) first in its list of storage goals in Table 1.6.1.2 on page 13 of its April 2015 draft. Like the Colorado Water Plan, the Arkansas roundtable BIP downplays PSOP, mentioning it only once in a fleeting reference to additional storage on page 204. In contrast, the Colorado River Basin Roundtable “advocates that TMDs should be the last “tool” considered as a water supply solution.” Colorado River Basin Roundtable BIP, March 17, 2015, draft, pg. 7, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1688062-cbrt-draft-bip-phase-ii-3-17-15.html, or for searchable text, see, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/1688062/cbrt-draft-bip-phase-ii-3-17-15.pdf. The Colorado Water Plan only mentions PSOP in its list of acronyms.

[31] Arkansas Basin Implementation Plan, January 2022, references the 361 projects on page 42 of Vol. 1, and lists them in a detailed spreadsheet on pages 104-109 of Vol. 2, but fails to provide no detail of the proposal to add 12 feet of concrete to each dam in order to hold back more water.

[32] The Eagle River MOU is described in a single line in the spreadsheet second from the bottom on page 104, Arkansas Basin Implementation Plan, January 2022, Vol. 2, pg. 104.

[33] Colorado Water Plan, 2015, Chap. 5: Water Demands, pg. 5-7.

[34] Fleck, J., Tashjian, P., Ish, C., McCarthy P., Oglesby A., ”New Mexico’s Rio Grande in the 21st Century,” The Water Report, Issue #243, May 15, 2014, pg. 5. Mexicali and Tijuana water use is reported in, Cohen, M., “Municipal Deliveries of Colorado River Basin Water,” June 2011, Pacific Institute, pg. 33-34, http://pacinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/crb_water_8_21_2011.pdf. Although residential water use is much lower in Mexico, farm water use is very reminiscent of U.S. farming north of the border in the Imperial and Gila River valleys. In the Mexicali Valley, 96.5 percent of the acreage was used to grow alfalfa, wheat, and cotton, and only 3.5 percent to grow carrots and asparagus for human consumption in 2008. Water use is likely even more skewed, as it takes more water to grow alfalfa than carrots. Alfalfa was grown on 62 percent of the Mexicali acreage under production. Brun, L, et al, “Agriculture Value Chains in the Mexicali Valley of Mexico: Main Producers and Buyers,” Sep. 15, 2010, Center on Globalization, Governance, & Competitiveness, pg. 6.

[35] Colorado Water Plan, 2015, Chap. 3: Overview of Each Basin, pg. 3-14.